![]()

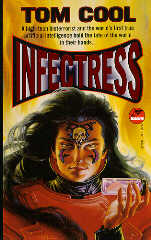

Love Theme of "Infectress"

Love Theme of "Infectress"I am Infectress,

mistress of the minuscule,

molecules,

secrets you repress,

truths too hideous

to express.

Kiss me,

beloved prey.

Entwine with me into one,

joined in hidden bond.

Secretly

I share

the molecular

engines of destruction.

Too tiny to taste,

they fit, exact,

to your demolition.

So I impart

life's nuclear lesson:

all your being,

your angelic seeming,

is as the genius

of a virus.

Kiss.

Life.

Nothingness.

Kiss.

Diane Jamison watched the four-year-old

boy scowl and cross his arms. He seemed to seethe as if all the world's fury focused in

his small frame.

So young, she thought. To have

so many demons, and all of them unchained.

Diane reached out toward Todd, but he

flinched. Slowly her hand lowered to her side.

They taught him to hate being touched,

she thought.She wished that her soul could broadcast into that tormented head and

illuminate him with her love, but she knew it was impossible. If humans had psychic

radios, Todd's receiver was tuned to static.

Diane and the boy stood atop a grassy

summit in the Laurel Mountains of western Pennsylvania. The sky was an unpolluted blue.

Down below, brilliant green deciduous forest, the successor of the aboriginal,

twice-timbered evergreen forest, stretched outward to all horizons. The mild sun of

northern summers warmed them gently. From the valley arose the shouts and laughter of

children less unhappy than Todd.

Since her disability retirement from the

FBI, Diane had begun volunteer work. As a big sister for poor children from Pittsburgh and

Philadelphia, she took them on retreats to this Christian camp high in the Laurel

Mountains. She believed that exposure to the beauty of the natural world would help these

inner-city children develop spiritually.

"I hate those mudderruggers,"

Todd said.

Diane knelt, facing the child. Eurasian,

Diane at first glance looked like an ordinary white woman, if striking, svelte and tall.

On closer study, her Asian heritage was suggested in the almond shape of her eyes, the

strength of her cheekbones and the touch of gold enriching her light skin. She placed her

hands on her knees. She tried to use her voice to project her love.

"Don't say that you hate them,

Todd," she said. "Say that you're angry. Hate is something that hurts you more

than it hurts them."

"I hate them. I wanna break their

heads."

Diane bit her lip. Finally, she said,

"It's hard, I know."

"Ain't so hard. Just hit 'em with

somethin' big. Bust 'em up. Lousy, rotten, no-good, lazy brats."

Diane realized that she wasn't listening

to Todd. She was listening to his parents, their abusive words echoing inside the young

skull, escaping through the young mouth. Then Diane realized she might be listening to

grandparents or great grandparents, voices from beyond the grave, shouted abuse echoing

down the tunnel of time, the only family legacy.

Her pocket computer beeped, startling her.

She had programmed it to interrupt her only in emergencies.

"Hold on, Todd," she said,

opening her pocket computer. She allowed it to register her retina, then read the

decrypted message:

FOLLOWING FITS THE PROFILE OF INFECTRESS CRIME:

The profiles she had built

into her home computer had alerted on a filed police report about an activity that matched

her model of Infectress. Anxiously, Diane read the police report, which stated that five

hours previously, San Jose police had discovered a man wandering along Highway 101. He was

George Leroy, American, white, 34, employed as the data systems security manager of

Paradigm International, which manufactured equipment for molecular engineering, mainly

gene splicers.

Leroy had been brain-wiped--illegal

surgery that left higher mental processes dysfunctional. There were telltale probe entry

wounds in the back of the neck. Blood and urine samples showed traces of caffeine,

nicotine, THC and AMT.

Diane looked up, only to see the distant

figure of Todd, escaping in full flight down the hill, down to the other campers in the

valley, leaving her alone on the summit.

She turned toward the south. She felt

sunlight on her face. A sun ray gleamed rainbows in her eyelashes. Diane concentrated on

breathing deeply, once, twice. In this way, she calmed her heart. She needed the calm to

find the courage to meet this challenge. To survive, she merely had to refuse the

challenge. Let someone else worry about Infectress.

For a long minute, Diane was sure that she

would let this opportunity, this danger, pass her by. Let the authorities handle it.

Then she remembered the wreckage from

United 310, which crashed in a cornfield in western Illinois. Diane had arrived on the

second day, after Infectress had published her manifesto claiming responsibility for the

midair explosion. The bodies had already been collected and stored in refrigerator trucks.

Searching for the principal investigator, Diane had entered the frozen interior of the

morgue truck. She remembered the chill across her exposed skin and the shivering of the

muscles over her ribs. She remembered the steel racks with the long rows of naked feet.

She remembered that one pair of feet, so small and doll-like. The toes were so tiny, so

perfectly formed. Since that day, the image of the dead child's unblemished feet triggered

again and again in her visual memory. Diane's eyes closed further. Now the sunlight

gleamed rainbows on tears.

It is wrong to hate, she thought.

But Diane knew one thing.

She hated Infectress.

Even if I die with my fingers around

her throat, I'll find and destroy that bitch.