|

AeroAstro Magazine HighlightThe following article appears in the 2009–2010 issue of AeroAstro, the annual report/magazine of the MIT Aeronautics and Astronautics Department. © 2010 Massachusetts Institute of Technology. ALUMNI INTERVIEW

|

||||||

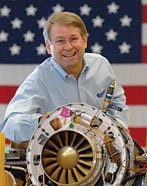

Langford with the Williams International turbojet that powers Aurora's Excalibur high-speed VTOL aircraft. |

|

It was a classic startup that took the few savings I had from my job at Lockheed, and that got us started in June of 1989 with two other Daedalus colleagues. We started in a little office in Alexandria, Virginia. And then Jim Anderson helped us get an "angel" investor who put in a couple hundred thousand dollars, and that helped launch the company and got us to the point where we began to win government contracts through the Small Business Innovative Research program, and one thing kind of led to another, and for the next five years for sure and almost through Aurora's was an absolutely impossible goal when we started is actually possible. Seventy percent is not as crazy as it sounds. It's not easy, but you can in fact get a 40 or 50 percent reduction with a re-optimization of the whole system. This team has had a great first phase. This is all still study work, but of course what Aurora hopes will happen is that NASA will find our ideas compelling enough that we'll be able to build a demonstrator airplane. We're not proposing that MIT and Aurora start building commercial transports, but we do think that the team that we've got can build a demonstrator. That's exactly what Aurora does and is in business to do. It would be a sub-scale demonstrator, which in this case would still be a pretty big airplane that could demonstrate the technologies that could produce 40 to 70 percent reductions in fuel use in future commercial airliners. Then, at that point, you obviously need to team with one of the major primes that's in the commercial aircraft business.

Q. What projects are you working on now that are related to energy and environment?

Langford: The current issue we're focused on is the melting of the Greenland ice pack. What we're working to do is take Jim Anderson's instruments and one of our airplanes and equip it with special radar that can see through the ice and measure the thickness of the ice pack and basically map it on a detailed basis and track it over time to find out how quickly it's going to melt. This is not just an area of academic interest — this is what blows my mind. What really brought it home for me was when Jim Anderson showed me a map of Cambridge that he had developed to show to his own board, and it showed how much of Cambridge was under water if the global sea level rises one meter, three meters seven meters. At seven meters, most of Harvard is under water. And if the ice pack all melts, it's seven meters. At three meters, MIT is gone. And we're not talking hundreds of years any more. There's evidence to support that it could happen in a century; there's even some evidence to suggest that it could be in the next 30 or 40 years. It's mind-boggling. And yet, the support is not there to even do the fundamental research. There's one little program here and one little program there. There's no systematic program to track and collect the measurements. And, it's still hard to get research money to investigate the state of the planet.

The U.S. government needs to re-focus its priorities for the issues that matter today. Unfortunately, it takes these cataclysmic events, like 9/11, to change these big bureaucracies. What we at Aurora want to see happen is that there has to be the same kind of focus on researching and measuring the environment that there is today on tracking terrorists. We've flown about 3 million flight hours with unmanned airplanes tracking terrorists because, in the post 9/11 world order, we are focused on individuals — where is a specific individual, what are they doing? We've developed the means to track them, and that's what robotic airplanes do. The utilization has gone from almost nothing to huge. But science flying is still about a thousand hours a year. It's a huge issue that this technology is here, but we have not found the national will to apply it, to take the measurements that we need to take, to figure out what the heck is going on with the environment. That's one of the great things about being back (working with) MIT. It's a way of pulling in the next generation of talent and enthusiasm to help us solve this problem.

Dick Dahl is a freelance writer who lives in Somerville, MA. He may be reached at rcdahl16@gmail.com.